Risk Can be Positive: 5 Takeaways from "Beneficial Risks of Experiential Education"

In his recent webinar "Beneficial Risks of Experiential Education," Steve Smith, Lead Consultant for Experiential Consulting, shared a science-backed perspective to how we can define and manage risk in our auxiliary programs. Here are 5 key takeaways that offer fresh insight and actionable methods to ensure your programs' safety while keeping them challenging and fun.

In his recent webinar "Beneficial Risks of Experiential Education," Steve Smith, Lead Consultant for Experiential Consulting, shared a science-backed perspective to how we can define and manage risk in our auxiliary programs. Here are 5 key takeaways that offer fresh insight and actionable methods to ensure your programs' safety while keeping them challenging and fun.

1. Risk Can Be Positive

How do we currently view the idea of risk? Do we feel anxious when talking about it? Do we feel constrained by risk-management policies? How confident do we feel when talking about the safety of our programs?

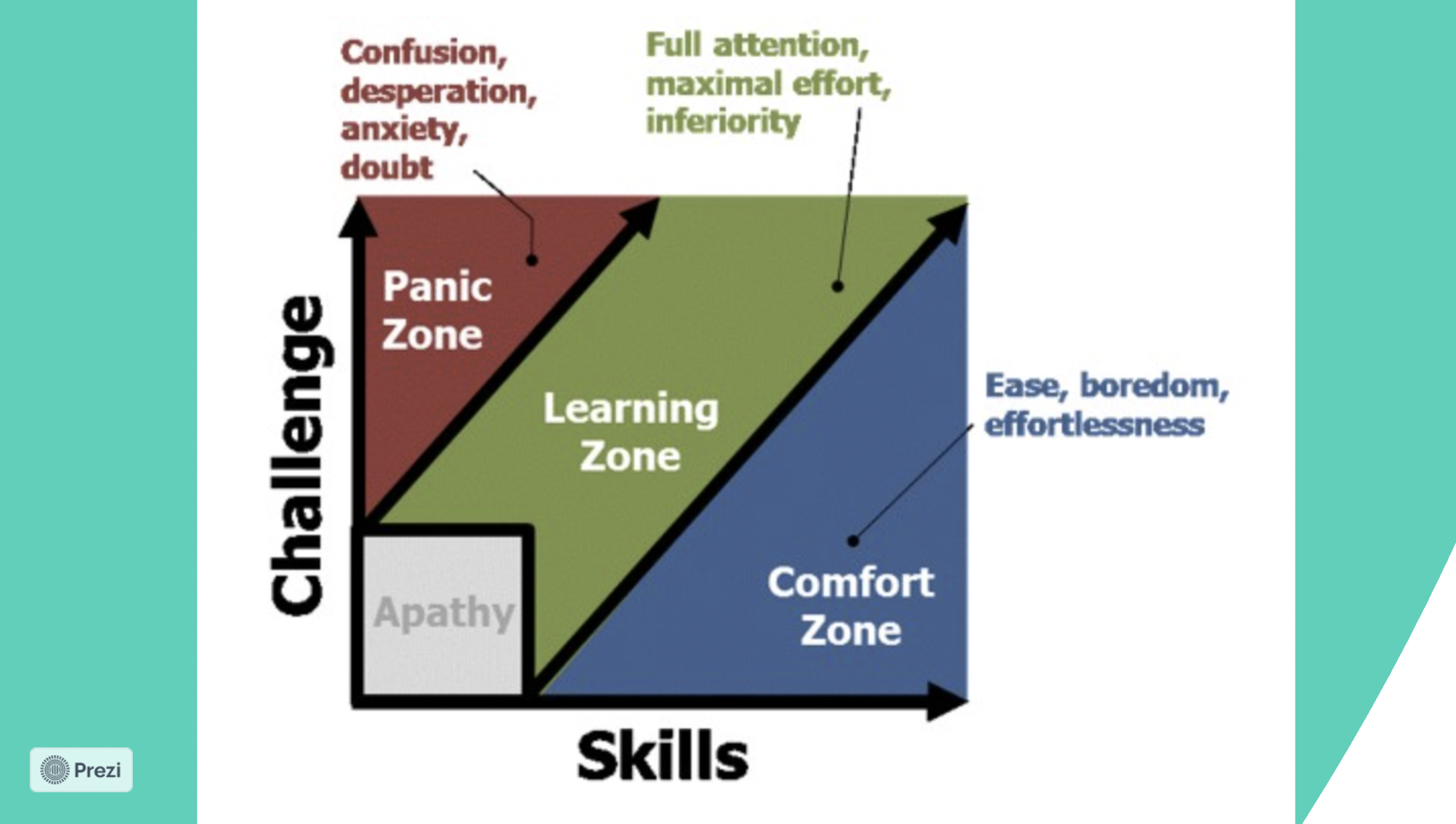

Steve defines risk as uncertainty with potential for either loss or gain and challenges us to change our mindset around risk. “We can think of risk as not a purely bad thing we need to manage and mitigate and transfer and pressure-wash out of our programs," he says. "Maybe risk is something we can integrate in a positive way. How do we optimize risk in a learning environment?”

The idea that risk can be a positive--that it can be intentionally worked into a program--opens up innovative ways of creating and managing experiential activities, especially when we understand that participants learn best when they are challenged and having experiences outside of their comfort zone.

2. Emotional and Physical Safety are Linked

There is an interrelationship between emotional and physical safety; they are not separate, siloed-off experiences. Emotional safety includes everyone involved in a program feeling safe to speak up when they have needs, questions, or concerns.

Steve cited an example from skiers taking avalanche training. "Studies show that groups that hear from everyone in the group make better decisions about skiing in avalanche terrain than groups that have a single autonomous leader," he says, "especially an inexperienced leader... and very interestingly, groups that have no leader at all make better decisions than groups that have a single autonomous leader.”

This takeaway is particularly striking--that the emotional safety of a group directly affects their physical safety, and If we're not ensuring emotional safety, we're not ensuring physical safety.

Steve identifies several indicators to look for to ensure emotional safety:

- Trust

- Transparency

- Ability to Voice Concerns

- Teamwork

- Vulnerability

What does emotional safety look like for us, and how does our school and programs foster it?

3. We Can Learn About Safety Every Day, Not Just When Incidents Occur

To maintain a positive mindset to learning about our programs' safety, we should focus on the big picture. Normally, we pay the most attention when something goes wrong--that's when we make changes. But Steve suggests we “ask the bigger question of what about that larger percentage of the time when things go right. Do we know why? Do we know why things normally go well?”

We don't need to wait for an safety incident to occur. We can learn every day by understanding why things go well and learning to do more of those things. One key question Steve encourages is, "were we lucky today? Or were we good today?"

4. Harness Brain Physiology to Make Better Decisions

Current scientific models illustrate how during the decision-making process, an ongoing tug-of-war exists between our limbic system—the brain's responses of fight, flight, or freeze when faced with perceived threats—and the prefrontal cortex, the brain's area for reasoning and rational thought.

Adolescent brains, however, engage in an unbalanced tug-of-war. "Their limbic system is fully developed and a hundred percent good to go at a very young age," Steve says, "but their prefrontal cortex is not fully functional at all until they’re approximately 25 years old. And some would argue that that’s getting older and older now.”

This imbalance is exacerbated by peer pressure, the absence of adults, the innate need to connect and be liked, and the desire to be popular or show off.

We tend to believe teens underestimate the hazards in a given activity, but that’s not actually the issue. In reality, Steve says, they're “overestimating the benefits that they’re going to get by jumping off that cliff, driving the car fast, impressing their friends, by being cool or whatever it might be.”

Studies show that "simply having the presence of adults in a group can help [teens] operate more from their prefrontal cortex than from their limbic system."

To help adolescents make better decisions, Steve recommends that we:

- Understand the tug-of-war

- Be aware of peer influence

- Utilize adult presence for a profoundly positive influence

- Realize pointing out hazards inadequate

- Engage adolescents in setting boundaries and rules

- Provide positive ways for them to meet their needs

5. Managing One Risk or Hazard May Unintentionally Create Others

Steve cites two case studies in which well-intentioned decisions meant to ensure safety led to unexpected risks.

In the first, the school instituted a policy that required all travel for off-site programs be completed before dark. Working from data that showed most travel incidents occurred after dark, the school believed this would decrease the possibility of accidents and better ensure the safety of participants.

In fact, travel became more hazardous as drivers increased speed or took routes that were faster or less safe in an effort to abide by the new policy. If the school had consulted those who worked in the field, they may have had the input necessary to devise a safer and more workable solution.

In the second example, newly-hired program leaders were required to call in every morning and evening from the field just to confirm everything was okay. Because the new leaders had little experience, it was believed safety was better ensured by mandating regular check-ins.

What they found was program leaders had to leave their programs for higher ground to find cell reception and meet the required check-in times. Sometimes, they had to leave participants unattended, creating a greater, unexpected risk. This is another case where all voices in a group needed to be heard before creating a policy that was focused on managing one risk.

To watch Steve Smith's complete webinar, click here: "Beneficial Risks of Experiencial Education"

Access webinars like this as well as weekly roundtables, practical tools, survey data, and more by becoming a SPARC member school today!